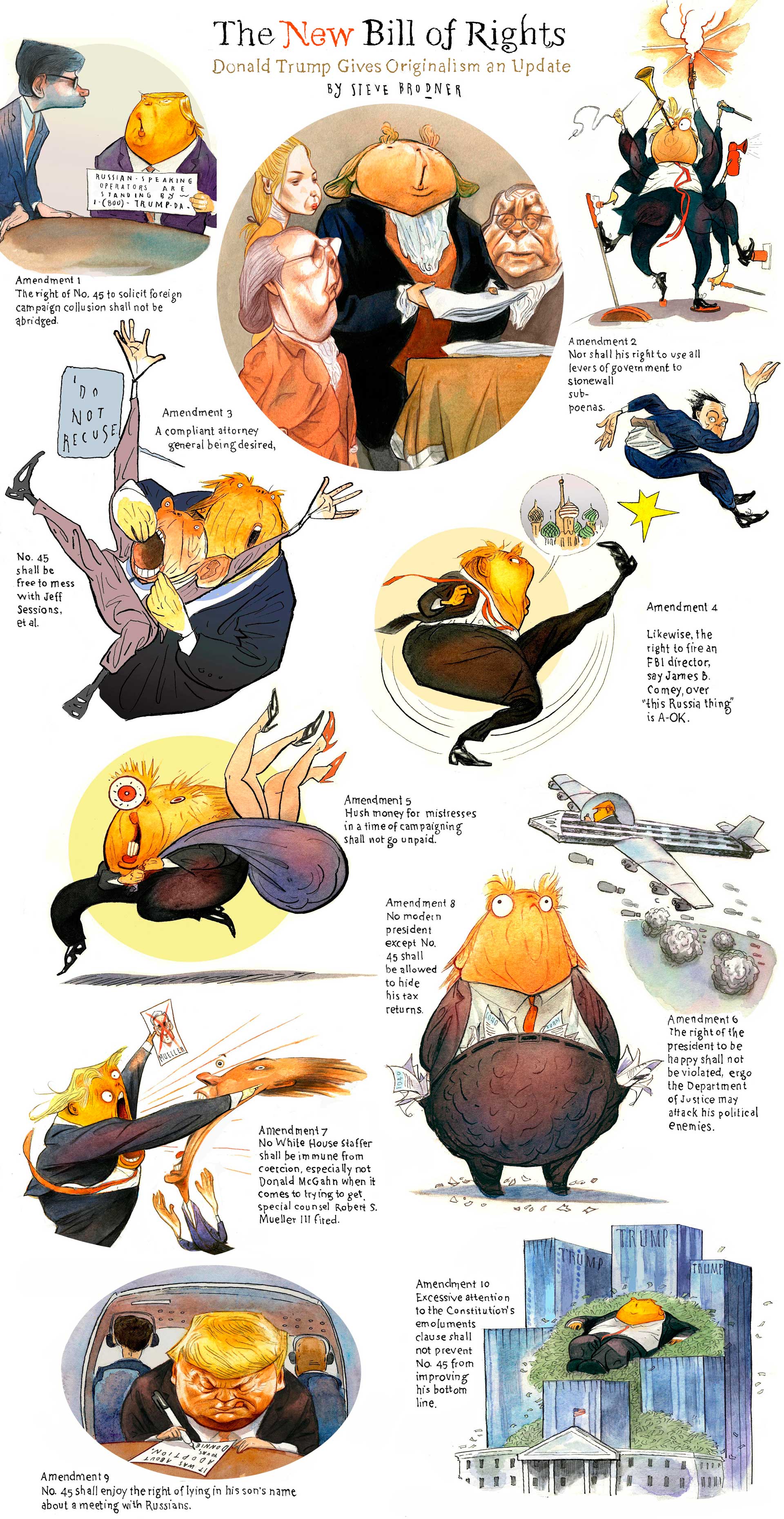

Here’s the Print interview from this month with Steven Heller and myself, complete with illustrations (first time trying that). Hope you like. Also a taped piece is running currently at MOTHER JONES. For guy who’s motto is: “Shut up and draw”, I certainly have been playing hooky. Back to work now, I promise.

DIALOGUE

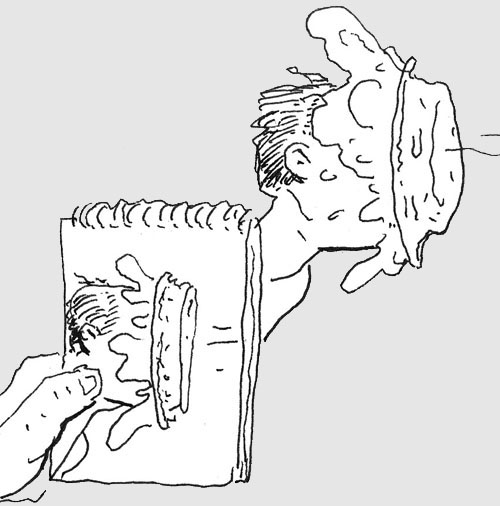

SB: A cute way of thinking

about caricature is like an inside-out sushi. The

sushi maker can skillfully arrange for the sticky

rice to be on the outside of the skin rather than

on the inside, where it usually is. A caricature

of anyone or anything can be rendered in a way

in which what is on the inside of a subject can

be brought to the surface. The story is most im-

portant to me here. There has to be a point;

otherwise, it’s a parlor game. Caricature is not

the train you get on, but the town you’re going

to.

SH: What is a Brodner caricature?

SB: It’s an attempt at visual narrative. My goal is always to

have the visual and literal messages blend so

well that you don’t see a difference. Like the

music and lyrics of a popular song, or in an

opera. When you are lost in the enjoyment of

the whole effect, the affair is seamless and

seems effortless; the mechanics disappear and

this then becomes a (good, we hope) experi-

ence for the viewer.

SH: Many of your caricatures

are politically motivated. Do you believe that

your art will have some impact on politics?

SB: Nope. I learned a long time ago that the point

of it has got to be the love of communication in

pictures with strangers about important things

in a way that has a chance to be meaningful

and compelling. How people react is up to them.

Some engage, some don’t. My job is to light the

lamp as best I can.

SH: How do you expect your

viewer or reader to respond to your art?

SB: know that people will encounter the art in

different circumstances,

coming from different places.

I want them to see it as honest: an at-

tempt by someone who has not gotten the

message that he ought to hide his feelings,

and who wants to contribute a concise and pas-

sionate assessment of issues before the public,

using visual language as effectively as possible.

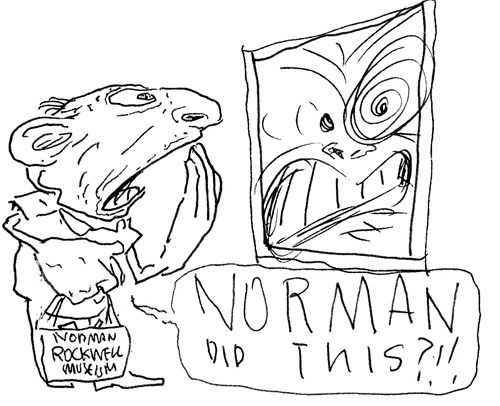

I was so gratified at the Norman Rockwell

Museum recently to meet conservatives who

were happy to talk politics because they saw

in the work an element of reason and sincerity,

even if, to them, it was wrongheaded.

SH: In this age when dirty tricks and negative campaign-

ing is so prevalent, how does a caricature make

any difference to the way people think?

SB: I think

caricature makes a difference when it has the

“of course” moment. This is when a very well-

realized idea is in the groove of the moment to

so great an extent that it crystallizes what peo-

ple are thinking, and because of that it cuts

right to the heart of a subject and does it with

a kind of grace. You see this in Hanoch Piven’s

portrait of Jesse Jackson with a speaker for a

mouth, Barry Blitt’s Obama/Osama cover for

The New Yorker, Victor Juhasz’s illustration of

George Bush getting an affectionate head-

knuckle from Jesus. When you see this happen,

you see something that is so dead on, you hit

your head and say, “Of course”—although in

Barry’s cover, it was a very taboo topic and made

people crazy. Also, there are a lot of people who

had never encountered satire in print before.

SH: You’ve been on a mission—one of those prover-

SH: You’ve been on a mission—one of those prover-

bial missions from God—to revive respect in

political art. Do you think you’ve succeeded?

SB: I do regular visits from God

because I have cable and Blue Moon beer in the

fridge. I complain about my lower back, global

warming, whether people will want political

art. She says, “Look, nobody cares about this

stuff. You draw pictures because you love it. So,

yeah, you’ll be rewarded for it. You’ll have the

pleasure in your work. And you’ll die happy and

go to the astral plane feeling like you didn’t

bullshit anyone and actually got to say true

things in print and online. Shut up and draw.”

SH: You’ve done some powerful images—one for

me when I was at The New York Times Book Review

of Joe Stalin with hands covered in blood—

and provoked a few angry letters (ironic, no?).

Have you been attacked at all for your work

during this past campaign?

SB: I don’t consider

disagreement or displeasure with a piece to

be an attack against me. There have been some

upset e-mails about pieces I’ve done—once,

somebody sent me a thing I did torn into tiny

pieces. You have to know it’s not about you. It’s

about the stories people have had already in

their brains. You sometimes become the moist

host for their insect eggs.

SH: You were given

a retrospective at the Norman Rockwell

Museum—a rare thing for a political artist.

How do you think this has changed the way

people perceive political art, if at all?

SB: When you

go up there and see people respond to your

work as a whole, it’s different than the reactions

you get to individual pieces. When they see

your trajectory of thought and sensibility, they

get a personal sense of you and are very warm to

what you are up to. Maybe that carries over into

the way they see our whole genre. That would

be nice.

SH: Do you consider yourself partisan?

SB: I’m clearly a person who thinks that people’s

problems can be solved by people. It’s hard to

deny that a considerable part of human endeav-

or has been devoted to coping and conquering

ignorance, illness, oppression, poverty. And

there have been tremendous strides, basically

because of people attacked as “liberal.” I feel

the pursuit of figuring out problems is worth

our trouble in this life. That would have to put

me in the progressive end of things. I don’t

think that keeps me from full-spectrum satire.

All politics is about part recognition, part

denial of true things. If we all focus on connect-

ing the dots of the latter, and have at ’em, we

will all be kept very busy.

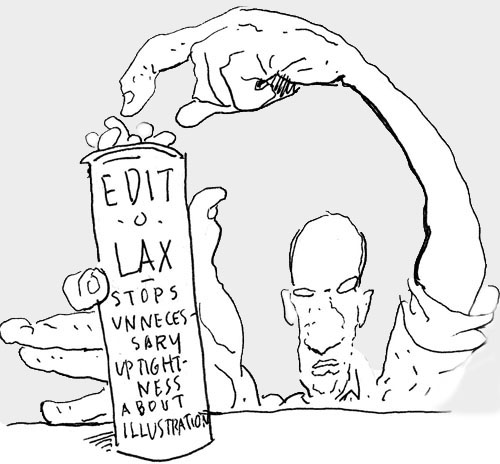

SH: You’ve offered

advice to editors and art directors on how to

strengthen the role of the visual satirist. What

would that be?

SB: To understand that we as a

graphic arts community have some very keen

points of view and powerful delivery systems.

We are authors and can be looked upon that

way. Most of the awards I have won have been

for stand-alone pieces that I have pitched to

magazines. Brad Holland, Barry Blitt, Sue Coe,

Bruce McCall, Joe Sacco, and others have shown

how this works. Engaging with us as authors

will keep approaches to coverage exciting and

illuminating for readers. Also, illustration

assignments usually come in at the last minute,

after the piece has been assigned to a writer.

Why can’t we get the assignment at the same

time? This would enable greater collaboration.

Greater amounts of time spent on work and a

much better scene for everyone.

SH: Do you

intend to do this—rage against the machine—

for the rest of your career?

SB: I’d be happy to go

to the end finding ways to tell the truth in

media as best I can. How can anyone not want

to do that?