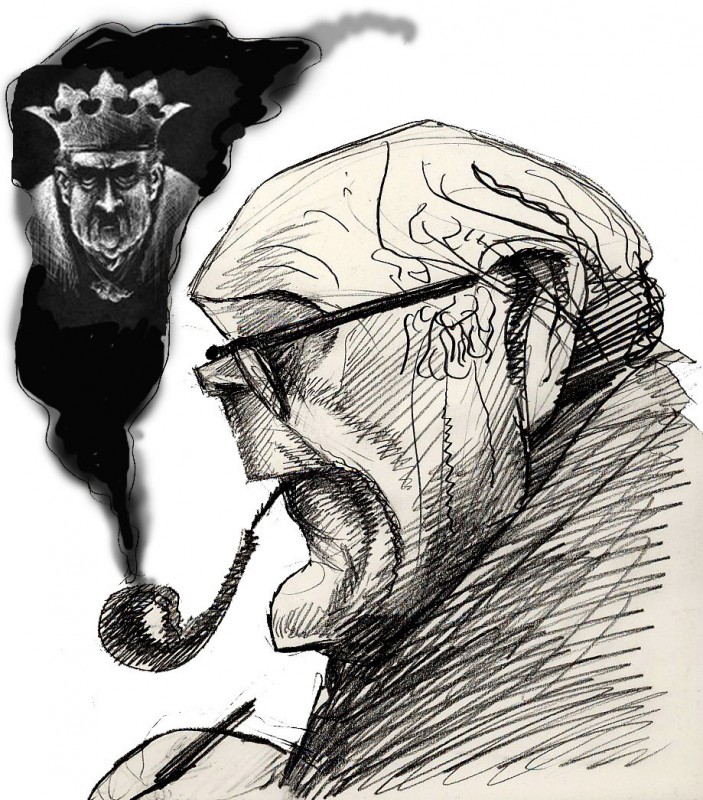

Paul Conrad, who we lost this weekend, was an idol to me and all caricaturists and cartoonists who wondered at the power of ink on paper as a force in the world. I slotted in here his Nixon as Richard III, a favorite of mine. His lines were simple but contained great energy and unraveled anger. He, Mauldin and Herblock were the big three who went into battle in America’s clearest moments of truth. Media played an important role. It was fact-based then. All three men had the power of major high circulation dailies behind them. There isn’t an equivalent today. LBJ and Nixon had as much to fear from the cartoonists as they did from the great editorial and column writers of the day. And Vietnam, Watergate and Jim Crow America were clear and vitally important targets. Conrad did us proud. And inspired this artist among many others. Below is the LA Times remembrance by his friend Tim Rutten and the complete doc on Paul by Barbara Multer and Jeffrey Abelson. Happy to present it here. Remembering Conrad today and always.

Paul Conrad was powerful, inspiring — and a friend

By Tim Rutten

He never lost his sense of outrage.

My friend Paul Conrad, who died Saturday at 86, was the premier editorial cartoonist of his generation and, for many years, this newspaper’s most visible public face. Outrage informed his journalism and animated his art. He woke up each morning angry about some new injustice and allowed sleep to overtake him each night only so that he could get up mad the next day and do it all again.

He was always and everywhere on the side of decency and ordinary men and women. His targets were the self-satisfied powerful, those indifferent to or antagonistic to our common good, and they included presidents — as in these cartoons — as well as governors, mayors, popes and corporate executives. Among his proudest accomplishments was making Richard Nixon’s enemies list.

Conrad had the strength to speak out so forcefully — through his incomparable drawings — because he was, in Yeats’ phrase, a “rooted man.” His values were rooted in the New Deal’s politics of remedy, in the social gospel of his Catholic faith and in the experience of the family he treasured beyond all else. The astonishing thing about his three Pulitzer Prizes was that he won them in three decades that were among the most tumultuous in modern American history. His willingness to engage our common condition, intensely and personally, was a hallmark of his work.

For those of us who came of age on The Times in the 1970s, he was an inspiration. Those of us who worked with him got up each morning hoping we’d live up to his example and knowing we’d fall short.