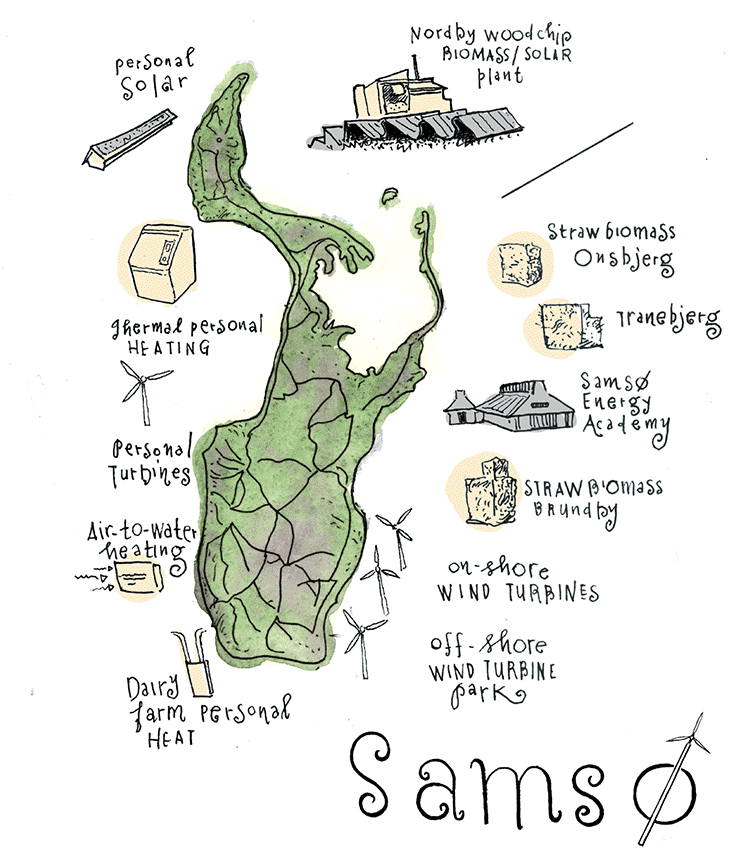

During our recent visit to Denmark Cynthia and I made a trip to Samsø Island, a place of miracles. In the late ’90’s the residents made up their collective mind to go green: develop existing renewable energy technologies to go carbon neutral and eventually carbon-free. In 10 years, not only were they CO2 neutral but were producing so much additional energy that they sold 25% of it back to the mainland . . . at a handsome profit. All this was accomplished with established tech: wind, solar, geo thermal, biomass. Clearly what they have achieved is easier in an island of 3700, where the wind never stops blowoing and the sun shines much of the year. But in a salute to the world leaders meeting now in Paris Len Small, Nautilus magazine, my amazing wife Cynthia and good pal Erik Petri (who both helped in countless ways) brought back this story, appearing now online as well as in four spreads in the upcoming issue. Great help also from editor, Ariel Bleicher. Hope this stimulates good ideas on our side of the pond.

During our recent visit to Denmark Cynthia and I made a trip to Samsø Island, a place of miracles. In the late ’90’s the residents made up their collective mind to go green: develop existing renewable energy technologies to go carbon neutral and eventually carbon-free. In 10 years, not only were they CO2 neutral but were producing so much additional energy that they sold 25% of it back to the mainland . . . at a handsome profit. All this was accomplished with established tech: wind, solar, geo thermal, biomass. Clearly what they have achieved is easier in an island of 3700, where the wind never stops blowoing and the sun shines much of the year. But in a salute to the world leaders meeting now in Paris Len Small, Nautilus magazine, my amazing wife Cynthia and good pal Erik Petri (who both helped in countless ways) brought back this story, appearing now online as well as in four spreads in the upcoming issue. Great help also from editor, Ariel Bleicher. Hope this stimulates good ideas on our side of the pond.

“The story began with Svend Auken, our brave Minister for the Environment,” says Soren Hermansen, who runs the Energy Academy on the Danish island of Samsø, an emerald comma in the Kattegat Sea. “When he returned from the United Nations climate change conference in 1997, he announced, ‘Now we need to start the green revolution in Denmark.’ That was very brave and very crazy.”

To get people excited about the idea, Auken set up a competition between municipalities for the best plan for going carbon-neutral in 10 years. When Samsø won, it became Denmark’s “renewable-energy island.” Hermansen, then a teacher, rock musician, and self-described rabble-rouser, took it upon himself to see that his native island lived up to its new name.

He brought consultants—and beer—to community meetings to try to convince his neighbors, many of them conservative farmers, to take up the cause. But the consultants weren’t getting through. So Hermansen sent them home. “Instead of telling people what they should do, I had to address the fear of change.” He told them that renewable technologies—wind turbines, solar arrays, biomass plants—would bring jobs and, better yet, money. Through subsidies, the government guaranteed a stable price for wind-generated power for 10 years, meaning investors could recoup their costs after seven or eight and start making a healthy profit.

That perked up their ears. Meeting by meeting, Samsingers—farmers, plumbers, schoolteachers, grocers—began to band together behind the project. When it finally got off the ground in the late 1990s, Samsø was putting 11 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. But by 2001, residents had cut their fossil fuel use by half. In 2003, they began exporting electricity to the mainland. Today the island produces from renewable sources 25 percent more energy than it consumes.

What makes Samsø’s story so remarkable, however, isn’t this fast transformation from carbon polluter to renewable-energy producer. It’s how it happened: Samsø owes its success not to a collective environmental idealism, but to its residents’ brass-tacks business sense.

“The wind always blows here,” Morton Holst, a grain farmer on Samsø told me. The steady resource allows the island to generate around 105 million kilowatt-hours per year with 11 land turbines, 10 offshore ones, and a smattering of micro-models. Residents use only about 24 percent of this electricity. They sell the rest.

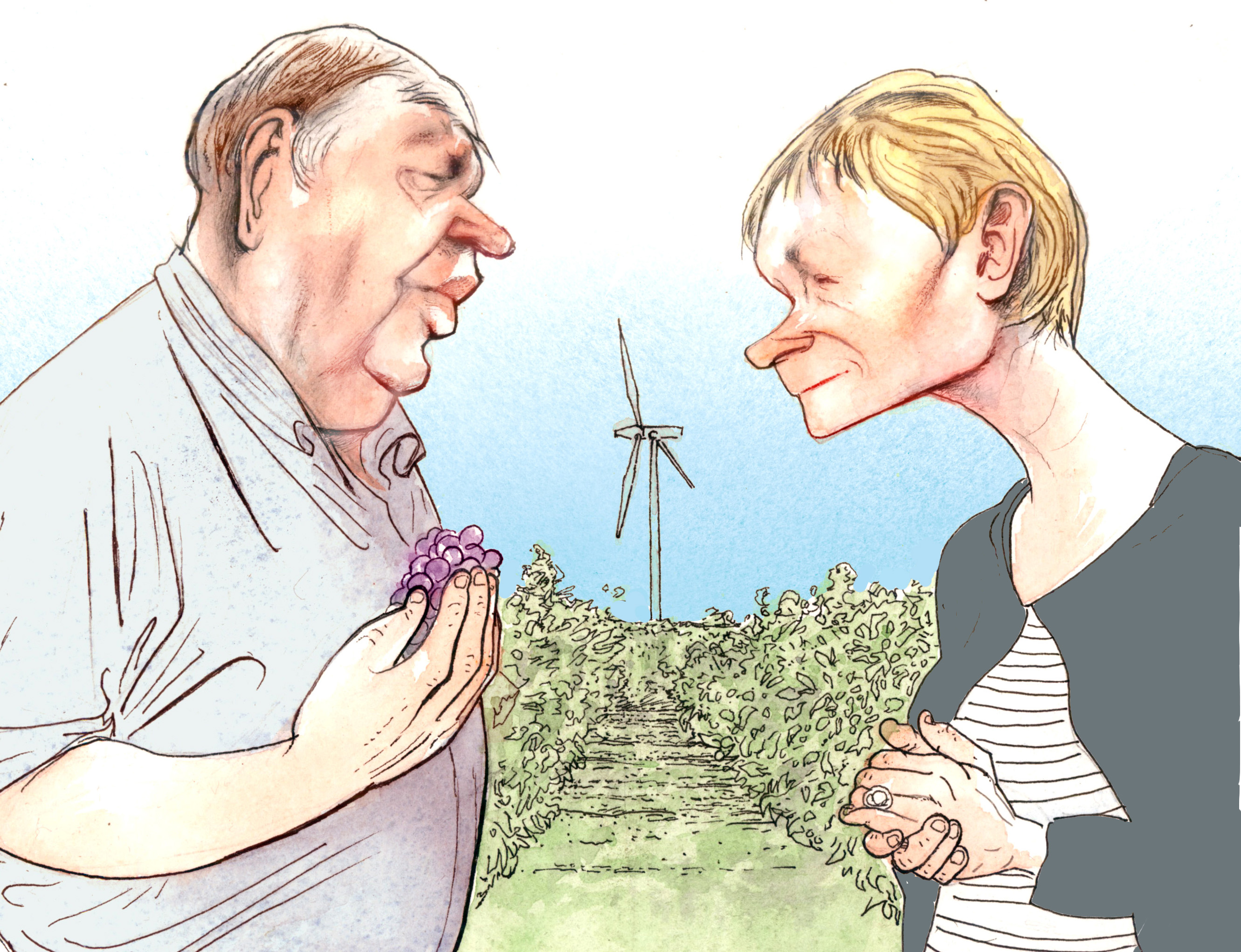

Ole Kaempe, a teacher on the island, and his wife Hedvig Hauge can see the turbine in which they invested from their farmhouse, whirring away beyond their vineyard. “Two of the wind turbines were offered to everybody; you could buy shares,” Kaempe says. “There was a lottery because too many people wanted in.”

Listening to the low drone of his turbine now, he says, he hears the “music” of income.

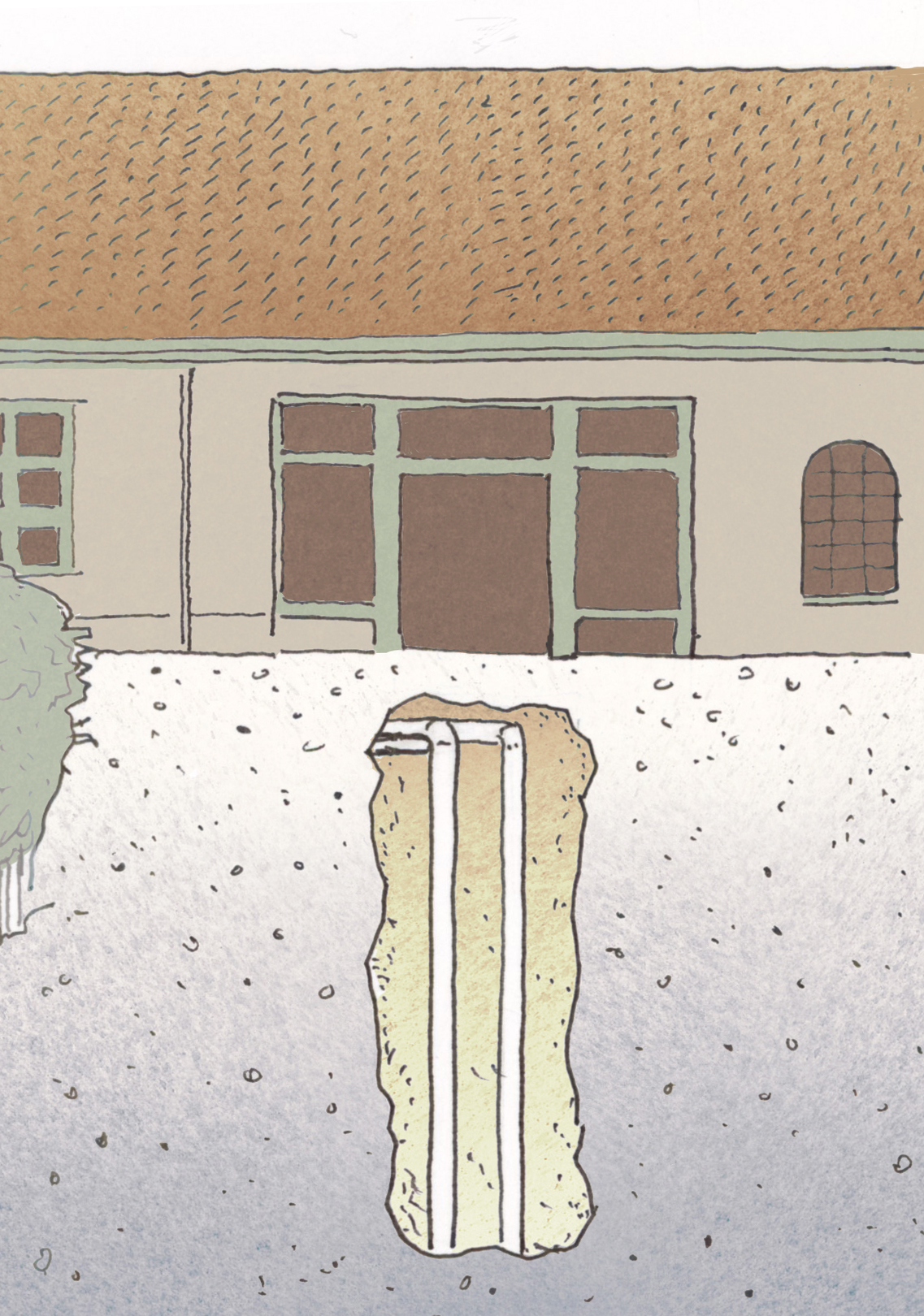

The geothermal pipes bring warm water up all winter. It moves through a pump which, when hit with refrigerant, results in very hot water, which then moves through internal heating pipes to radiators in their home.

Two decades ago, most Samsingers heated their homes with oil hauled in on tankers. Then Hermansen and others got together and calculated that residents could save up to 50 percent on their heating bills if they replaced their furnaces with pumps that drew hot water, through underground pipes, from district heating plants.

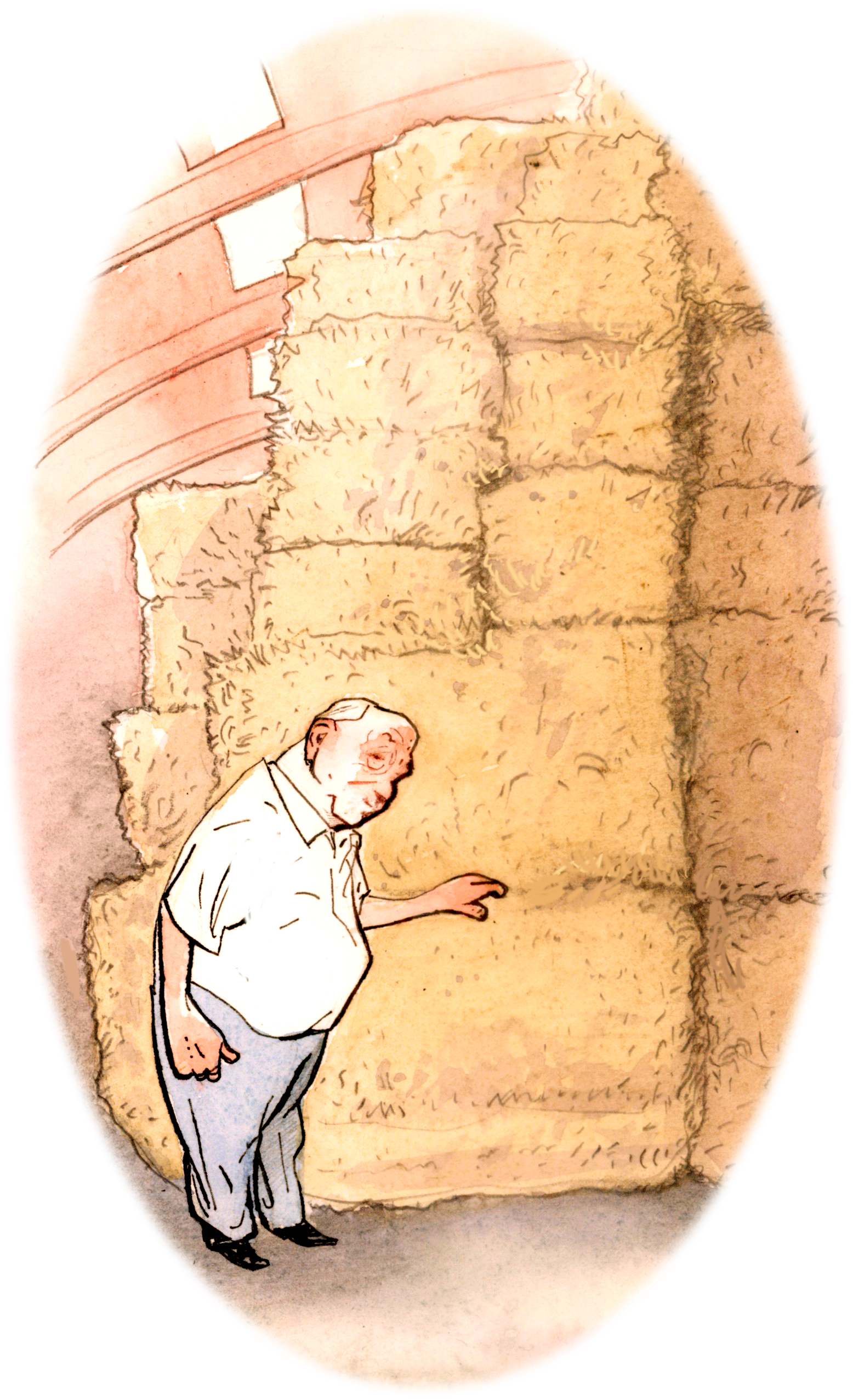

Arne Jensen runs three plants fueled by straw bales, which he buys from local farmers. (A fourth plant burns wood chips.) “It takes two and a half kilos of this stuff to replace one kilo of oil,” he says. “This plant processes 1,600 tons a year. If they replaced that with oil, they would have to spend 20 million Danish krones [about $2.9 million], five times as much. That would be 20 million going out of the community. Instead, the money stays here.”

Here’s the track the straw moves on. It gets chopped very fine and sifted before burning.

The Kiln. Believe me, it is hot.

The process is also, more or less, carbon neutral. The CO2 released during burning simply displaces the carbon that would have entered the atmosphere naturally, as the straw decomposed. Even the ash is repurposed as fertilizer.

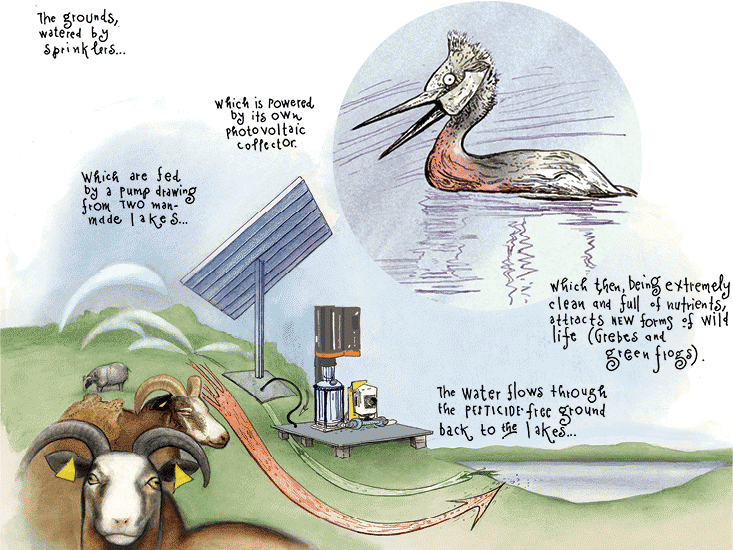

Samsø Golfklub, tucked in the island’s northeast corner, is a kind of microcosmic showcase of the community’s embracement of sustainability. The club’s carts and mowers are solar-powered, and golfers carry hand-held weeders so they can do spot maintenance as they play.